Where the Diamond Was Born

Every great tactical idea has a lineage. You can’t truly wrap your head around what this system is trying to do until you understand where it all started. It’s a story that begins way before Johan Cruyff ever laced up a pair of boots a story of radical ideas that were so far ahead of their time, the rest of the world spent the next fifty years just trying to catch up.

The Pioneers of Fluidity

Long before "Total Football" became a household name, we had the Magical Magyars. The Hungarian side of the 1950s—the Puskás and Hidegkuti era—played with a positional freedom that left traditionalists scratching their heads. Their forwards didn't just stay up top; they dropped deep. Their midfielders didn't just sit; they charged into the box. Every player on that pitch was a footballer first and a specialist second. They were, in the most literal sense, the first Total Football team, doing it a decade before we even had a word for it.

Then you’ve got Ernst Happel, a man who is still criminally underrated in the history books. Before Michels or Cruyff were lifting trophies, Happel led Feyenoord to the European Cup in 1970. He was obsessed with positional overloads and the idea that sheer intelligence could out-muscle raw athleticism. You can’t tell this story honestly without tipping your cap to him; he laid the bricks for everything that followed.

The General and the Architect

It was Rinus Michels who took these sparks and turned them into a wildfire. At Ajax and with the legendary 1974 Dutch national team, "The General" codified the chaos. His central principle was as simple as it was devastating: if a defender steps up, a midfielder drops. If a winger drifts inside, someone else fills that space from deep. The pitch wasn't just a patch of grass; it was a breathing organism where everyone knew everyone else's job.

And then, of course, there was Johan Cruyff.

First, he was the player who gave Michels' system its soul—the man who could see the geometry of a pass before anyone else had even spotted the run. But in 1988, as manager of Barcelona, he took those lessons and built the "Dream Team" 3-4-3 Diamond. This was the ultimate evolution. You had Ronald Koeman acting as a Libero who stepped into midfield like a playmaker; a central diamond that absolutely dominated the middle of the park; and a young Pep Guardiola sitting at the base, dropping into the defensive line the second possession was lost.

It was the most complete version of Total Football we’ve ever seen at the top level. Absolute width, absolute depth, and total control. That era is our North Star, the foundation for every single click and instruction you’re about to see in this FM26 guide.

"In my teams, the goalkeeper is the first attacker and the striker is the first defender." - Johan Cruyff

Introduction

A Philosophy, Not a Replica

Let’s get one thing straight from the jump: this isn’t a tribute act. The history I’ve just walked you through tells you where the spark came from, but what follows is a continuation, not a copy-paste. The principles belong to Cruyff, but the tactic breaks his "rules" in three very specific, very deliberate ways that we’ll get into shortly.

The big breakthrough for FM26 is a single, powerful concept: one starting XI, two completely different shapes.

In possession, we are a 3-4-3 Diamond. It’s expressive, fluid, and built on "bounce passes"—first-time combinations that zip the ball through the lines before the opposition even realises they’ve been bypassed. But the moment we lose it, we shift. We become a compact 4-3-3 press. It’s aggressive, it’s organised, and it’s designed to trap the opponent inside. And here’s the kicker: when we win it back, we don't just hoof it on the counter. We reset. We get back into our diamond and attack at full strength, every single time.

I haven't just tinkered with this in a vacuum. I’ve run the gauntlet with it at Arsenal, Barcelona, and Roma, picking up league titles along the way. But the real proof? Taking York City out of the National League on an £80k budget, playing the most dominant, high-possession football the fifth tier has ever seen. The same diamond, the same soul, regardless of the level.

The Core Innovation: The Dual-Shape System

This is the "secret sauce" for FM26. We’ve moved past the era of static formations.

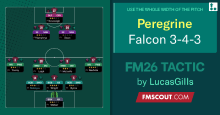

With the ball: You’re looking at a 3-4-3 Diamond. It’s all about overloading the middle of the pitch while our wide players stretch the play before cutting in to cause absolute chaos.

Without the ball: We snap into a compact 4-3-3. A high line, a fierce counter-press, and a defensive trap that forces the ball into the areas we want it.

It sounds complex, but in practice, it’s seamless. You don't need a different set of players for each phase; you just need the right roles. By choosing specific roles that naturally "gravity shift"—like our DLP dropping into the backline—the team evolves its shape in real-time without you having to touch a single slider.

The transition from a 3-4-3 Diamond to a 4-3-3 press. As possession is lost, Timber drops to right-back, the IFs track back, and Zubimendi anchors the midfield: three moves, one unit—a living structural shift in real time.

The Arsenal Setup: Protecting the Core

At Arsenal, my priority was keeping that world-class partnership of Saliba and Gabriel together in the heart of the defence. I didn't want to break them up just to play a diamond.

So, I used Timber as my tactical bridge. When we were in possession, Timber pushed up from the backline to sit at the base of my 3-4-3 diamond as the DLP. He became the pivot, the man who dictated the tempo and gave us that crucial +1 advantage in midfield. But the second we lost the ball, the out-of-possession instructions kicked in. Timber would drop immediately into the Right-Back slot.

This was the "Eureka" moment: Timber’s natural versatility allowed us to defend in a rock-solid 4-3-3 with a traditional back four, but attack with the suffocating pressure of the diamond. Saliba and Gabriel never had to leave their comfort zone. Timber did the legwork so they could stay as the "Twin Towers" in the middle.

The Barcelona Setup: The Pure Cruyffian Pendulum

When I took the reins at Barcelona, the solution had to be even more central to the club’s DNA. I looked at Frenkie de Jong and saw the modern-day reincarnation of the Guardiola role.

In the possession phase, Frenkie was my DLP—the conductor at the base of the diamond. Everything went through him. He was scanning, zipping those "bounce passes" into Pedri and Gavi, and essentially running the show. However, my defensive transition at Barça was different from the one in London.

When we lost possession, I didn't want Frenkie heading for the touchline. Instead, I had him drop straight back into the Centre-Back position. This triggered my wide centre-backs (like Koundé or Araujo) to fan out into the fullback zones. We shifted from that attacking 3-4-3 Diamond into a compact 4-3-3 defensive block with Frenkie anchoring the heart of the defence. It was pure poetry—a playmaker defending as a libero, then instantly becoming the architect the moment we won the ball back.

Why It Works for Me

In both cases, I wasn't just clicking buttons on a tactic screen. I was using the FM26 "In and Out of Possession" logic to exploit the specific strengths of my best players.

Whether it was Timber sliding to the flank or De Jong dropping into the spine, the result was the same: my team always had the perfect shape for the moment. We were never "caught" between formations; we were simply evolving in real-time.

The System at Work

This is the whole idea: provoke pressure, bounce through the diamond, then go vertical. Rice first-time, Gyökeres ruthless.

The assistant manager's summary tells you everything: "Timber was at the heart of everything good in the middle, exchanging a total of 176 passes with his team-mates, and linking up with 9 other players."

176 passes exchanged with 9 different teammates from the base of the diamond. This is midfielder output. This is what the DLP pivot produces when the system is working: the central node through which every sequence flows. The pass density around Timber was the highest on the pitch because every triangle in the diamond connects back to the base. He is not just a ball-winner. He is the conductor.

This is the bounce pass chain starting at its very first link. The ball does not go long. It goes short, to a player who already knows his next pass.

This is the Play Through Build-Up instruction made visible: Playing short with a playmaker dropping deeper to provide an extra passing option, opening the option to play the diagonal out wide if building through the middle is not possible.

The moment possession is lost, Ødegaard, Rice, Zubimendi, Gyökeres and the surrounding players collapse into a tight swarm around the ball carrier John Stones in this case. Seven Arsenal players within a few metres of the ball, all pressing simultaneously. This is the Counter-Press instruction working in real time: no transition, no retreat, immediate aggression. Cruyff said when you lose it, attack to win it back. This is that.

Ødegaard, Rice and Zubimendi are all in frame behind the press, positioned to intercept the forced turnover. This is the Trap Inside instruction in practice: the wide press triggers from the outside and angles the ball carrier inward, where the diamond's three playmakers are already waiting. Lewis has nowhere to go that can not go through Trossard.

The out-of-possession 4-3-3 in its clearest form. Timber (#12) is visible in the upper half of the pitch; he has dropped from his DLP position at the base of the diamond into the right-back slot of the back four. Zubimendi (#36) is the holding midfielder at the base of the 4-3-3 midfield three.

Arsenal The Data

Three radar charts from the Data Hub tell the full story. Here are the numbers, honestly reported, including the one weakness the system carries as the price of its aggression.

The 21.4 dribbles per game is one of the most satisfying numbers in the dataset. It is proof that the More Expressive instruction is functioning exactly as intended. Players are taking players on, making decisions, and expressing themselves within the structure. This is not structured for its own sake; it is structured to give intelligent players the freedom to be brilliant.

The defensive radar has one amber figure: Arsenal concede a above average number of final third passes against them per game. The Head Performance Analyst flags it directly. This is the price of the high line and the aggressive press. When the press is beaten, the opposition reaches our final third more often than a conservative team would allow.

Here is why it does not matter: the other defensive numbers absorb it. 0.7 goals conceded per game. 0.9 xGA against. 16 clean sheets. The 4-3-3 defensive shape, the Trap Inside instruction, and the compact back four handle the exposure once the ball reaches the final third. This is not a flaw to fix; it is a known trade-off that the system manages. Cruyff always understood that aggressive football carries aggressive risk. What matters is the outcome. 0.7 conceded per game is the outcome.

The 87.4 possessions won per game is the counter-press working. The 15.8 PPDA opposition passes per defensive action confirms how aggressively we engage out of possession. These numbers tell you the 4-3-3 press is not passive. It hunts.

Total domination domestically.

Where This Diverges From Cruyff

Three Ways This Is Deliberately Different

The tactic takes inspiration from Cruyff's philosophy but departs from it in three specific, deliberate ways. These are not compromises; they are design decisions that make this system distinctly original. Understanding them is essential to understanding why the tactic works the way it does.

1. Bounce Passes — Progressive, Not Patient

Cruyff's Barcelona could sustain long possession sequences — recycling sideways, switching play with Koeman's long diagonals, waiting calmly for the moment to open. This tactic does something fundamentally different: it progresses the ball rapidly up the pitch through quick bounce passes. The ball arrives, leaves immediately, comes back, and goes forward again. Every pass has a forward intention, not patience for its own sake, but rapid progression through combination play.

Much Shorter Passing combined with Higher Tempo and More Expressive produces exactly this. Players move the ball before the opposition press can reorganise around them. Triangles are not formed to recycle — they are formed to break the first line of pressure and advance. This is why the pass map shows dense clusters of short interlocking passes in the central zone: not a patient sideways game, but an upward one built on speed of thought and touch.

2. No Counter-Attacking — A Measured Reset Instead

Cruyff's teams would often counter immediately after winning the ball — his philosophy was aggressive in both directions. Press to win it, then immediately exploit the disorganisation before the opposition resets. This tactic consciously rejects that approach. When possession is regained, we hold shape, reset into the 3-4-3 diamond, and attack with the full system fully set.

The reasoning is specific to this formation. The 3-4-3 is already aggressive — three attackers, three midfielders pressing high, wide centre-backs advanced. If we counter from this shape, we leave the back three exposed to exactly the rapid transition we have been defending against all game. By resetting instead, we force the opposition to face the complete diamond, fully organised, every single time we attack. They never get the transition contest. They always get the full system.

This is the most significant philosophical divergence from Cruyff. But it is not a compromise — it is the logical consequence of having built an attacking formation this aggressive. You protect it by refusing to let the game become a game of transitions.

3. Three Playmakers in Midfield — Intelligence Over Industry

Cruyff's diamond used technically gifted but physically demanding wide midfielders — players who combined quality with work rate and defensive discipline. Amor, Nadal: intelligent, but not pure playmakers. This tactic uses three players of genuine playmaker profile: the DLP at the base, the AP on one side, and the MPM on the other.

The effect is a midfield of extraordinary combined intelligence. Width is held not by runners pushing beyond the ball but by the playmakers' positional awareness; they understand when to stretch and when to compress, when to provide the bounce pass option and when to play forward. Three playmakers in the diamond means three players capable of finding the give-and-go, the one-touch combination, the exit pass that breaks the press at any moment. It makes the diamond almost impossible to press effectively. There is always someone who finds the solution — because all three central midfield players have the intelligence to be that someone.

This simultaneously achieves two things Cruyff always wanted but approached differently: width is maintained through positional intelligence rather than raw running, and the centre is controlled through quality rather than numbers alone.

"Playing football is very simple, but playing simple football is the hardest thing there is."

Johan Cruyff

Team Instruction

If you’re looking for the one instruction that defines this entire philosophy, this is it. Forget the roles and the fancy triangles for a second—Hold Shape is the heartbeat of the tactic.

In a world where every "meta" FM tactic is obsessed with the lightning-fast counter-attack, I’ve gone the other way. When we win the ball back, we don't sprint forward like headless chickens. We don't "Counter." Instead, we pause. We reset. Every player returns to their designated station, and we rebuild the 3-4-3 diamond from the ground up. The opposition never gets to play a "transition game" against us because we simply refuse to invite one. They are forced to face our complete, settled system every single time we cross the halfway line.

The Logic of the Reset

Why be so disciplined? The reason is dead simple: this is already an incredibly aggressive formation. With three attackers pinned high, three midfielders pushing up, and wide centre-backs bombing forward, we are essentially "all-in" on every attack.

If I told the team to counter from that position, we’d be naked. A loose pass during a fast break would leave our back three completely isolated, defending vast oceans of space behind the press. That’s exactly how you get hurt in FM26. By choosing to reset, I’m trading the possibility of a cheap, fast goal for the certainty that we attack at full strength, with our defensive safety nets (like Timber or De Jong) exactly where I need them.

Where I Break with Cruyff

This is probably where I diverge most sharply from Cruyff himself. Johan’s teams were happy to counter; he was aggressive in both directions. But I’ve taken a more measured approach.

I don't counter I measure. I reset the board, and then I strike on my own terms. And don’t run away with the idea that this makes us slow or boring. Because of the Bounce Pass system we’ve built into the passing instructions, the "reset" happens in the blink of an eye. We move the ball so quickly that the opposition still hasn’t caught their breath by the time the diamond is strangling them again. We just do it with the structure intact.

"If you have the ball, the opponents cannot score. When you lose it, attack immediately to win it back."

Why Arsenal The Perfect Fit

I’ve tested this system across four different clubs at four very different levels of the pyramid. From the high-pressure cooker of the Camp Nou to the muddy realities of York City, the diamond has held its own. But if you’re asking me where this tactic truly "sings" where it feels the most natural and plays with the least friction, the answer is Arsenal.

It’s not just down to the massive transfer budget or the reputation of the club. It’s about something deeper: the culture, the way the squad is built, and a tactical DNA that stretches back to Cruyff in an almost unbroken line.

The Philosophical Lineage

Let’s look at the family tree. Cruyff coached Guardiola at Barcelona. Guardiola then took those ideas and refined them into the most dominant "positional play" system in modern history. Mikel Arteta spent years as Pep’s right-hand man at City, absorbing those same principles, the importance of the pivot, the high press, and using the goalkeeper as an extra playmaker.

The Arsenal squad is practically a custom-made toolkit for a dual-shape system. You have players like Jurriën Timber, who is the absolute "unicorn" for this tactic. He has the brain of a midfielder and the recovery pace of a fullback. You have David Raya, a keeper who’s probably better with his feet than half the midfielders in the National League.

Everything about the way Arsenal have recruited in recent years points toward this kind of flexibility. At other clubs, I would have to spend three windows trying to find players who could handle two roles at once.

Squad Depth: Every Role Covered and Competed For

The 3-4-3 Diamond is a demanding system. It requires nine distinct player profiles performing nine distinct functions. At most clubs, one or two of those roles has no genuine competition — one player, no backup, no pressure. At Arsenal, every role has a real competitor for the shirt. The squad depth Arteta has assembled means that if Timber is unavailable, the system does not break it adapts without dropping quality. This matters enormously across a long Premier League season, and it is one reason this tactic suits Arsenal above all other clubs.

Four Clubs, Four Levels, One Philosophy

Look, a tactic that only works when you’ve got a billion-pound squad isn’t a philosophy it’s just a lucky coincidence of quality. To really prove this system wasn't a fluke, I had to put it through the ringer. I tested it across four different clubs at four completely different rungs of the footballing ladder, and the results were staggeringly consistent.

I took it to Arsenal in the Premier League, Barcelona in La Liga, and Roma in Serie A. We didn't just compete; we picked up league titles at all three. But the real litmus test? York City. I’m talking about the National League, the fifth tier of English football, working with a tiny £80k transfer budget on pitches that are more mud than grass.

Even there, the "Total Voetbal" DNA held firm. We won promotion via the play-offs, playing the most dominant, high-possession football the division had ever seen.

Whether I was managing world-class superstars at the Camp Nou or part-timers in North Yorkshire, the results were identical. The same diamond. The same rapid "bounce-pass" tempo. The same seamless dual-shape transition. It didn't matter if it was Timber or a lad on 400 quid a week; the geometry of the game stays the same. If you give players a clear structure and the freedom to express themselves within it, the system can work for you.

One hundred points. Unbeaten. 121 goals—the highest tally in La Liga. We averaged 63% possession, more than anyone else in Spain. Raphinha ended the season as the highest-rated player in the league, bagging 27 goals and 19 assists from that wide position. The numbers were staggering, but it was a single news headline mid-season that actually stopped me in my tracks: "Guardiola spotted at Camp Nou."

There he was. The man who sat in that very same pivot role under Cruyff all those years ago, sitting in the stands watching a tactical system inspired by his own mentor’s philosophy, right at the ground where it all began. They say history doesn’t repeat, but in that moment, it definitely felt like it was rhyming. Seeing the "Dream Team" DNA translated so perfectly into the FM26 engine at the very club that defines it was the ultimate validation of everything I was trying to build.

This is the model: attract the press, drive through the first line, then find the free man, Olmo, arriving off the blindside.

Looking at the overhead view, you can see the orange lines highlighting the exact 3-4-3 Diamond we’ve been building toward:

The Hub: Frenkie de Jong (#21) sits at the base left of the diamond, orchestrating the build-up.

The Midfield Engine: Gavi (#6) and Pedri (#8) flank the central space, while Dani Olmo (#20) sits at the tip of the diamond. They aren't just standing there; they are creating a net of passing options that makes it impossible for Sevilla to get a sniff of the ball.

The Wide Support: You can see Balde (#3) and Koundé (#23) providing the width, stretching the pitch so the diamond has room to breathe in the middle.

The red zone shows the space that opens up around De Jong at the base of the diamond. Koundé passes low "towards the feet of Jules Koundé" while De Jong occupies the space between the lines. The three playmakers ahead of him draw opposition pressure upward, leaving the DLP in acres of space.

Here you see Frenkie de Jong (#21) dropping straight from that deepest pivot role into the heart of the defensive line. He isn't just "defending"; he's occupying the central space to complete a compact back four. As he drops, you can see the wide centre-backs (like Koundé #23) beginning to fan out, preparing to cover the flanks.

It’s the Guardiola Role in its purest form: the midfielder who becomes the emergency centre-back the moment the ball is lost. This is exactly why the 4-3-3 defensive block works so well; it doesn't matter that we've been attacking with bodies everywhere. The moment the whistle blows for a transition, De Jong provides the structural "snap" that turns an expansive diamond back into a brick wall.

This image captures the In Possession phase perfectly. We aren't defending here; we are dictating.

The Pivot: Frenkie de Jong (#21) is exactly where Cruyff would want him—sitting at the base of the diamond, just ahead of the back three. He isn't a defender here; he’s the heartbeat, providing the "two passing options" that allow us to recycle play or pierce the lines.

The Overload: By having De Jong step out of the defensive line to anchor this diamond, we create a numerical nightmare for the opposition. We have four players in the central corridor, forcing Sevilla to either collapse inward and leave the wings open, or stay wide and get carved apart through the middle.

This is the " expressive" side of the tactic. It’s built on those rapid bounce passes that progress the ball before the press can even find its shape. When you see De Jong positioned like this, you’re looking at a team that has total control of the rhythm.

Frenkie de Jong (#21) is anchoring the system. In this phase, he occupies the deepest pivot role, acting as the "heartbeat" of the 3-4-3 Diamond. From here, he has a 360-degree view of the pitch, ready to trigger a rapid "bounce pass" sequence or drop straight into the defensive line as a centre-back if possession is lost. It is the modern-day reincarnation of the role Pep Guardiola perfected under Cruyff.

The Space to Run Into: Exploiting the Final Third

This is what "Total Voetbal" is all about: the payoff. We’ve spent the whole match building the diamond, recycling possession, and exhausting the opposition's press. Now, the trap is sprung.

As Alejandro Balde holds onto the ball in the middle of the pitch, you can see the secondary effect of our structure. By overloading the central corridor with the diamond, we’ve sucked the entire Sevilla defence into a narrow, panicky block. This creates a massive ocean of space on the flank the exact space Pedri is about to ghost into.

This is the exact moment the "Hold Shape" philosophy transforms from a defensive safety net into an offensive weapon. Look at the green shaded zone that is our Counter-Pressing Trap.

The second the ball is loose, we don’t retreat. Because the 3-4-3 diamond keeps our players so naturally close to one another in the central corridor, we are already perfectly positioned to swarm. Gavi (#6), Pedri (#8), and De Jong (#21) have effectively formed a high-intensity cage around the ball carrier.

The goal here isn't just to win the ball back; it’s to deny the opposition a single second to look up and find an exit. By squeezing the space as a unified block, we force a panicked clearance or a direct turnover. It’s high-risk, high-reward football that only works because every player knows exactly which lane to shut down. We don't just press the man; we delete the options around him.

Conquering the Tactical Heartland: My Roma Campaign

Serie A has a reputation for being the most tactically sophisticated league in Europe. It’s a landscape defined by defensive organisation, physical intensity, and a deep, historical suspicion of open football. It’s the ultimate testing ground for any philosophy. My 3-4-3 Diamond didn’t just survive the Italian gauntlet; it completely dominated it.

We finished the season as champions with 82 points, boasting the highest goal tally in the division and adding the Europa League trophy to the cabinet for good measure. What made this so satisfying wasn't just the silverware it was the fact that I refused to compromise. I didn’t adapt the system to suit the Italian style; I forced Italian football to adapt to me. Whether we were facing a low block in Naples or a high press in Milan, the diamond provided the answers, proving that "Total Voetbal" is a universal language that even the world's best defenders can't translate in time to stop.

The Fingerprint Identical Across Every Club

The same two amber figures appear at Roma that appeared at Arsenal: fouls above average and final third passes against above average. This is not a coincidence; it is the system. The high line and aggressive press produce both numbers at every club where this tactic is run. And at Roma, as at Arsenal, the outcome numbers absorb the exposure: 1.3 conceded per game in one of Europe's most competitive leagues, with the most goals in the division. The pattern is consistent. The philosophy is real.

This is the pattern: stack the right side, drag them narrow, reset through Mancini… then the punch pass into Malen once the lane opens.

The Roma Build-Up: Precision in the Europa League Final

This is the system at its most disciplined, proving that the diamond can be just as clinical in a major European final as it is in a league match.

The Defensive Diamond: You can see Mario Hermoso and Mancini forming the base of our build-up structure. They aren't just clearing the ball; they are looking for the "bounce pass" options to maintain control.

The Pivot Relationship: N. El Aynaoui occupies that crucial space just ahead of the defenders, acting as the bridge to the midfield. By forming this diamond deep in our own half, we ensure there is always a safe triangle available to recycle possession.

Structural Maturity: This image captures why we dominated Italy. While most teams would be panicking or sitting in a deep block, we are comfortably stretched across the pitch, using our positional superiority to kill the game. We aren't just holding a lead; we're holding the ball.

The Dropping Striker: Look at Evan Ferguson (#9). He’s not playing as a traditional target man pinned against the centre-backs. Instead, he’s dropped deep into the "10" space, becoming the apex of our central diamond.

Creating the Overload: By vacating the front line, he forces the Nottingham Forest defenders into a lose-lose choice: follow him and leave a massive hole behind them, or stay put and let us have a 4v3 advantage in the most dangerous part of the pitch.

The Connection: You can see the clear white lines connecting Ferguson to Manu Koné, El Aynaoui, and Pisilli. This isn't just a midfield diamond anymore; it’s a total-team diamond that incorporates the attack.

This is the "Cruyffian" ideal in practice. The striker becomes a midfielder, the midfielders become runners, and the opposition is left chasing a shape that refuses to stay still. It’s exactly how we managed to dismantle the most disciplined defences in Serie A.

The two red arrows show the runs opening up behind Forest's defensive line, the space the CHF role is designed to create. The striker stays high and pins the last defender. When the striker drops (previous image), that pin is released, and these runs become available. Pisilli is looking for Malen's movement into the red zone. The system's cause and effect are shown in two consecutive frames.

Anyone can make this philosophy work with Timber, Ødegaard and Gyökeres. The real question is whether the system is genuinely sound or just exploiting squad quality. York City in the National League answers that question. The fifth tier of English football. £80K to spend. Basic analysis staff. A squad assembled from free transfers and loan players. The same 3-4-3 Diamond. The same bounce-pass philosophy. The same dual shape.

The fingerprints are identical. Most goals in the league. Most possession in the league. 89.1% pass completion from a squad assembled for £80K. Daniel Batty, a National League midfielder flagged by the analyst as performing well above average in creativity. That is the three-playmaker diamond working at the fifth tier: the system creates creative output from players who would not normally produce it, because the structure around them makes them better.

York City were predicted to win the league. A poor run of form in the final weeks of the season cost the title — Carlisle took it on 91 points. But 3rd place with 85 points and 103 goals, promoted through the play-offs, with the most goals and most possession in the division: this is the philosophy working with next to nothing. At Arsenal, it is a system. At York City, it is a proof.

This is the pattern: isolate wide, hit the byline, attack the six. One error from the keeper and it’s a tap-in.

Batty drives into the right channel and pulls the ball back rather than crossing high. Nathaniel-George arrives in the green zone to meet it. This is the Low Crosses instruction producing exactly what it promises, and Batty, a National League midfielder, is executing it because the system has put him in exactly the right position to do so. The attack started from the diamond. The cutback is how it ends.

Even at York City, with a fraction of the budget and a squad playing at the fifth tier, the "out-of-possession" logic remains bulletproof. This image perfectly captures the team’s defensive transition as we protect a 3-0 lead in the 90th minute.

The Back Four Transformation: You can see the defensive line has snapped back into a rigid, traditional back four. Just like the systems at Arsenal and Barcelona, the central player has dropped from the pivot to anchor the defence, allowing the wide defenders to tuck in and secure the flanks.

Proof of Concept: This is the ultimate validation of the philosophy. Whether it's world-class professionals in La Liga or hard-working specialists in the National League, the dual-shape system provides the same level of security. We dominate with the ball in a diamond, but we survive without it in a rock-solid bank of four.

Olley winning the header over Saunders, with N. Lawrence and the York press clustering behind him, the white convex hull showing the compact swarm around the second ball. This is the Get Stuck In and Counter-Press instructions working in combination: York don't just press the first ball, they position to win everything that comes off it. National League opposition. Premier League pressing logic.

The De Jong Moment History Repeating Inside the Tactic

The Barcelona adaptation produced the most historically resonant detail of the whole project. Frenkie de Jong plays as the DLP pivot in possession — the technical intelligence at the base of the diamond. Out of possession, he drops back into the defensive line as a centre-back, completing the back four.

This is precisely what Pep Guardiola did under Cruyff at Barcelona. The midfielder who dropped into defence. The intelligent player who occupied two structural roles within the same match. I did not plan this historical echo. The system produced it naturally because the logic of the DLP role demands exactly this kind of positional intelligence. When I saw De Jong dropping into defence in the same way Guardiola had done thirty years earlier, it felt like the tactic had found its own place in a much longer story.

"Quality without results is pointless. Results without quality is boring."

Why It Works The Honest Verdict

The best tactical systems in Football Manager are not the ones that exploit the match engine. They are the ones that make internal sense, where every instruction, every role, every shape decision follows logically from the one before it. This tactic makes sense. The DLP drops into defence because it completes the back four numerically. The IFs track back because they are already inside and close to the defensive line. The wide CBs push high because the DLP's positional intelligence covers the space they vacate. Hold Shape on transitions because the system only works at full strength.

Everything connects. Nothing is arbitrary. That coherence is what makes it work across three different clubs, three different leagues, and three different squad profiles. The diamond is not the point. The philosophy behind the diamond is the point.

Cruyff understood that better than anyone. This tactic tries to honour that understanding, in its own way. It is not his tactic. But it learned from him.

Ultimately, the success of this system across the Premier League, La Liga, Serie A, and the National League proves that tactical geometry is the great equaliser in football. Whether you are managing elite technical innovators at Arsenal or battling for every inch of grass at York City, the principles of the 3-4-3 Diamond provide a universal framework for dominance. It is a tactic that rewards patience, values structural intelligence, and remains steadfast in its belief that the right shape can solve any problem on the pitch. By embracing this philosophical lineage, you aren't just downloading a formation; you are implementing a way of playing that honours the past while ruthlessly conquering the modern game.

![FM26 2025-26 Real Fixture & Results [19-2-2026]](https://www.fmscout.com/datas/users/realresult_thumb_25_26_fm26_257759.png)

Discussion: Cruyff Inspired Total Football 3-4-3 Diamond

No comments have been posted yet..